Visual Journalism

(Introduction to the Visual Communication course that I taught for 38 years at the University of Minnesota and Indiana University.)

What is visual journalism? It is the marriage of word, pictures and sound.

Every journalist or public relations practitioner should be able to practice visual journalism. The job market demands that you are one. What skills do you need to be one?

An accomplished writer and image-maker has the ultimate flexibility in telling a story with the greatest impact. When motion is an important element in conveying information to your audience, you will choose video. When emotion in the voice is important, you may choose still pictures with a soundtrack. You may well use words and pictures in print and a video or an audio slideshow on the web.

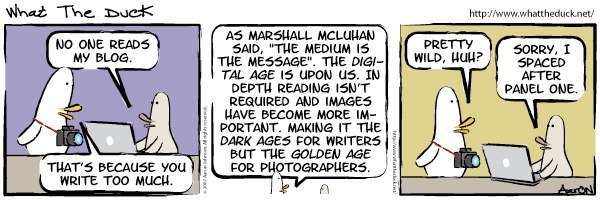

Students historically have entered the journalism programs with a preference for what they want to do in their careers. Those intended careers have had a presumed skill set, and, to a certain extent continue to do so. But, the silos that separated journalists who produced in words from journalists who produced in images and sound are falling. If you want more than anything to write, you will concentrate on crafting precise, compelling, grammatically correct sentences using AP style.

If you want the body of your work in journalism to be visual, you need to master capturing the moments that move people emotionally, that help explain situations that are difficult to describe in words, or that preserve history.

Students who enter a school of journalism must recognize that the communications world today requires you to acquire—and polish—as many skills as possible to be competitive. Aspiring writers have to be able to produce photojournalism, video story telling and multimedia presentations. Photographers have to be able to gather information and present that information in words. You may not excel in all skills, but you have to be professionally competent in all. The job market now will tolerate no less.

The most important aspect of communication—knowing how to report a good story—is the same regardless of the technology you plan to use to tell that story. You must know how to sell story ideas to editors. Don’t wait to be told what to do. Create your own assignments. Journalists with ideas become indispensable. Those who wait to be told what to do will join the ranks of the unemployed.

Technology enables you to produce the story for the appropriate distribution channel. But, technology cannot make the decisions. Without your brain, technology cannot produce a good story. Too often, journalism majors are naïve about what is going on in the university, city, nation and world.

If you do not read, you have no chance of succeeding in this field. I might add you will also have little chance of succeeding in most other fields as well. Reading is the beginning of the process. Next you have to think about what you have read. What questions were raised but not answered? What are the really important unexplored questions? These become story ideas for journalism classes. They become term paper topics in other university classes. An informed person will have no end of ideas to explore.

This course continues your exploration of verbal and visual communication skills leading to a major portfolio piece. Writing improves with practice in writing. Story-telling in images gets better by shooting.

This is one reason the School of Journalism now requires students to have their own cameras. You need it with you at all times so that when you see a visual story, you can capture it.

Your camera will help you “see” details that are so important for a compelling story. This course will help you “see” where you formerly only “looked.” Seeing is a process of taking in, and remembering, both macro and micro detail in a scene. You become aware of how a person is dressed, whether perfume is present and what scent, whether the man was clean-shaven. whether the hair is wind-blown, etc. Diane Ackerman is a writer who writes “visually.” See if you don’t have a picture in your mind when reading this passage from “A Natural History of the Senses.”

“While real penquins porpoised beside the boat, huge icebergs floated by, with bases of pale blue and sides of mint green. In the ship’s glassed-in observation deck, people sat in armchairs at the window, some dozing. One man held out his pinky and first finger as if giving someone the evil eye, but he was measuring an iceberg.Deception Island, though distant, looked close and clear in the sterile air. A crib of ice holding a soft blue wash in its palms drifted close to the ship. Across the strait, ice calved off a glacier with a loud explosive crumble. Pastel icebergs roamed around us, some tens of thousands of years old. Great pressure can push the air bubbles out of the ice and compact it. Free of air bubbles, it reflects light differently, as blue. The waters shivered with the gooseflesh of small ice shards. Some icebergs glowed like dull peppermint in the sun—impurities trapped in the ice (phytoplankton and algae) tinted them green. Ethereal snow petrels flew around the peaks of the icebergs, while the sun shown through their translucent wings. White, silent, the birds seemed to be like pieces of ice flying with purpose and grace. As they passed in front of an ice floe, they became invisible. Glare transformed the landscape with such force that it seemed like a pure color.” (A Natural History of the Senses, pages 234-235)

Ackerman writes visually and coincidentally this excerpt is on her chapter on vision. She is a writer who “sees” what is around her and remembers her surroundings in vivid detail. Notice how much you learned in this short passage so beautifully written.

As you photograph, you too, will see more detail than you have before. Really looking at what is around you will make you both a better photographer and writer.

Your own education

You will find a new emphasis in the School of Journalism on making sure you are a partner in your own education.

We will teach you fundamentals of good journalism, the foundation for your future. But, you will have to learn how to teach yourself in the currency of journalism.

You will have to explore self-education of software packages on your own. What we cover in journalism classes is only a beginning. The campus provides free software courses and you should explore them. You must learn software as a component of your professional development and preparation for your career. You must learn the tools of your trade as ongoing homework.

When you leave here, if you have invested in your education, you will leave with current tools and the knowledge of how to continue to educate yourself. But, remember this: The communications world is changing so rapidly that the currency of your education in technology will be dated within a year or less. That is why you have to learn how to teach yourself to remain competitive.

Learning Style

Some cognitive psychologists suggest that half of us learn better when material is presented visually. The groundbreaking eye-track studies conducted by the Poynter show how important visuals are in print and on the web. In a newspaper, readers’ eyes move first to a photograph, then to the photo caption, and then to the headline. This is the point where writers’ impressions of how their stories are read diverge from data. Writers think that readers read their stories from the beginning to the end.

They don’t.

Frequently, after the first few paragraphs, the reader moves on to another photograph and another story. The inverted pyramid style of writing actually conditions the reader NOT to read the story completely. The essential information is in the first few paragraphs.

Strong writing with multiple photographs about a compelling topic can help move readers to the end of the story. Compelling visuals with sound will hold reader attention on the web.

Developing the story line

A visual journalist’s attention will be torn from one focus to another. If you are writing your notes, you can’t make pictures at the same time. If you are shooting video, and your eyes see a great still picture, too bad. (Technically, it is now possible to pull a publishable still from video but the quality is not yet comparable to a good still camera.) If you are holding a recorder for sound, you can’t be making video or stills.

It is a little like triage in medicine. You make judgments in the field about what you should be doing and when. Yes, you will make errors of judgment but you will do the best you can. If your job requires both writing and multimedia, you will gather the information, pictures and sound you need. You will put the story together using what you have, not what you would have had if three assistants and two interns were helping you.

Be open to change

When you leave for an assignment, you may have done some preparation or someone else may have done it for you. Sometimes, even often, the situation on the scene is not as expected.

You have to deal with what is, not what was expected. This often means improvising in the field. You may have to go to a hardware store and get raw materials to make and mount a remote camera system on a helicopter as I once did as a college student. Rethink problems into opportunities.

Just “G-R-Done,” as Larry the Cable Guy would say.